LUCY

Where is my mind? The Pixies asked the ultimate question in that famous song. Where IS my mind? And what is in it when I delve a bit further than the initial surface of daily routine? I’ve recently been getting interesting results from using pen and watercolour sketching and a semi-meditative state to discover the answer to this question.

My first step on the path to even exploring this was starting a mindfulness course a few years ago. I have subsequently taken the same course 4 times and am now beginning to explore further the many varieties of meditative techniques. Even just a few months of daily basic mindfulness meditation has given me a taste of how it feels to explore my own consciousness. I’m already far less skeptical than when I started, and the idea of meditating in my room is actually more of an attractive prospect than going out on the town! The concept is so ridiculously simple and obvious, I’m almost ashamed I haven’t just always done it. It’s unbelievable that modern life is so overwhelming that we have to re-teach ourselves just to stop; to actually listen to our own bodies and minds. Ironically for such a self-obsessed society, we don’t actually take much notice of our true internal voice.

Through this regular meditation I’ve had a number of interesting experiences, often dream-focused. I find that when I meditate I almost immediately return to a recent dream, I can’t change anything, so its not what they call ‘lucid dreaming’, but I’m in it, I can walk around it and explore it, and I get the same feelings and emotions I had when i was having it. My dreams now are different, they feel more like experiences than dreams and give me a strange sense of having been somewhere.

Quite by chance, I recently started doodling when I was focused on other things, as a stress release. I found that letting my instinct guide me resulted in some interesting imagery. As soon as I started regulating myself – ‘don’t put that line there’ etc. the pictures were far more dull and without the sense of freedom they had encompassed before. I tried to go back to the other technique and found that I could utilise the relaxation part of the mindfulness practice, but without switching off completely. Let the pen guide itself and do exactly what it wants. Don’t limit it, don’t think about what might look good or bad; basically don’t allow your conscious mind to impose the very limiting boundaries which are born of external influence.

The result is these images. I see these as an early experimentation phase, what might grow from further practice at this technique is yet to be discovered. It’s the first time I have not had to labour at a piece of art, the first time I haven’t had to ‘try’, haven’t had to worry about the end result. Releasing myself of that anxiety allows me to truly enjoy the process and I think that probably comes through in the imagery.

All works are pen and watercolour on paper and are for sale.

Visit my profile at Art Market Direct to purchase.

I paint naturally. From when I was a child I’ve been able to draw and paint and I don’t need anybody to tell me to do this or that, I just know what to do, I just do it. I don’t have to think about it, I know instinctively what’s going to work – Peter Roland-McLean

Soho. 1960-something. The Colony Club. Hazily drunken escapades with a dreamteam-esque artistic collective whose members include Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon, John Deakin. Undoubtedly up there in the top 5 moments in history someone with my artistically hedonistic curiosity would gleefully type into a time machine should I one day stumble upon one. Artists and actors, debauchery and creativity. Sounds sublime. But, as one member of this in-crowd was to discover, extreme high times such as these can soon be a fast track to the very low.

Today, at 73 and having battled alcoholism and drug addiction for many years, artist Peter Roland-McLean is now clean and in recovery with the continued support of both AA and NA. Living in Greenhithe in Kent, most of his time is spent immersed in a world of oil and memory within his studio/bedroom, with an eye-catchingly beautiful auburn cat named Mr Ben as assistant, a chatterbox the artist confides is ‘sometimes a bit of a bully’.

Contemporary, student and friend of Lucian Freud, Peter has produced a number of portraits of the renowned artist; a significant influence not only in his work, but throughout his life from their initial meeting at Camberwell College in 1958 up until his death in 2011. He speaks of Freud fondly, a mischievous twinkle in his eye as he recalls how they ‘talked about art and the situations we’d get into through the boozing’. Although hints of Freud’s impact can be detected, the stylistic uniqueness of Peter’s works and the skillful ability to infuse a scene so deeply with hypnotic dynamism is all his own.

With a father who spent 22 years in the army, Peter, at 18, found himself undertaking an unsurprisingly disastrous period of national service. With artistic temperament rarely well-received in a disciplinary setting, he synopsises the experience as ‘some idiot shouting at me’, a sentence I can entirely imagine myself uttering in the same circumstances; “There were some things so ridiculous they were telling me to do. I said hang on a sec, you can shout as long as you like but I’m not doing it. So in the end they said I was crackers and discharged me, which was the best thing that happened to me in the army”.

At this point – 20 years old and acutely aware of his passion for painting, “the only real interest I had was all-consuming really, it was painting and drawing. I just knew, right from the beginning”, he joined Camberwell College of Art on a three year Fine Art course under the tutelage of an as yet relatively un-recognised Lucian Freud. They became friends, both in and out of the college surroundings, and Peter was soon part of the fashionable clientele drinking regularly at The French House on Dean Street and the legendary Colony Room fronted by the infamous Muriel Belcher. Francis Bacon was a customary fixture at the bar, with one of his most well-known paintings being a portrait of its afore-mentioned matriarch. It was around this time that Bacon’s work was beginning to seriously take off and his philosophy on material and media left a lasting imprint on Peter’s work; “Bacon used to talk about the accident. I look for that sometimes and if it happens, I don’t take it out. Oil paint; It’s magic, you can work it in, you can push it about, do wondrous things with it. Sometimes I’ll be that engrossed with the painting that I’m not really looking at the palette and I put the brush in the wrong colour and put it on. I’ll leave it on. I have this idea that it’s meant to happen”.

The 60’s Soho scene was infused with alcohol and drugs; Bacon and Freud themselves were heavy drinkers and others in the group gradually became seriously dependent. Peter’s artistic output became less substantial, with frequent intoxication affecting his creative abilities and subsequently his general daily life. He soon became homeless and spent a significant amount of time living on the streets of Central London, experiencing the harsh realities of a life of drug dependency.

Through reflection and documentation of his past life experiences, Peter draws his subject matter from his memories, building emotionally charged scenes on canvases thick with deeply worked oil; ‘I can’t handle acrylic, it makes me feel sick’. Whether inhabiting the smoky rooms of the French, propping up the bar at the Colony Club or disappearing into the shadows of St Martin’s, the characters dominate the composition; enlarged extremities draw the eye, expressive countenances carved like fleshy rock stare confrontationally out at the viewer. Peter confirms that these are true representations of those who frequented the clubs, there’s ‘Gypsy John, he’s an old Romany fellow, used to drink in the graveyard up at Southwark’ or ‘Tambourine Billy, who used to bang the tambourine down the tube. People would give him pennies, but he still had enough at the end to get a bottle of wine or something’. Others document well-known characters such as Amy Winehouse or Nigel Kennedy, ‘I liked him because he’s mad as a march hare’, whose maniacal glance shoots from the canvas whilst he plays his violin, exaggerated hands dominating the foreground. Most viewers of Peter’s works will notice the way in which his brush renders the human hand; a recurring theme in almost all of his pieces. The emphasis on these extremities and their often disproportionate size is not, as I initially guessed, indicative of menace or violence, a tool to accentuate the unsettling overtone present in the scenes, but instead the manifestation of his feelings about how we as a society take hands for granted. Hands, he says ‘are so important and yet people don’t pay much attention to them’.

Despite the clear and vast differences in their works, Peter and Lucian have much in common, an affinity not only for paint and the beauty of art, but a kindred zest for excess and enjoyment, an embrace of the risque which ignites their work but would take its toll on the rest of their lives. ‘If I drink again, I’ll die’ he tells me, yet is equally pragmatic about how lucky he is to still be here, to have the friends and companions he has and to still be painting. Throughout his life, in spite of the ups and downs, his desire and instinct to paint remains constant, an inherent necessity rather than a choice. He is a natural born painter, a fact recognised early on by Freud, who told him off the record that he did not need to be tutored, he knew exactly what he was doing. 54 years later, it’s clear that he still does.

All artworks by Peter Roland-McLean

Photography by Kate Withstandley

For information about the upcoming exhibition follow me on Twitter (@artexplorer434) where I will share details when they become available.

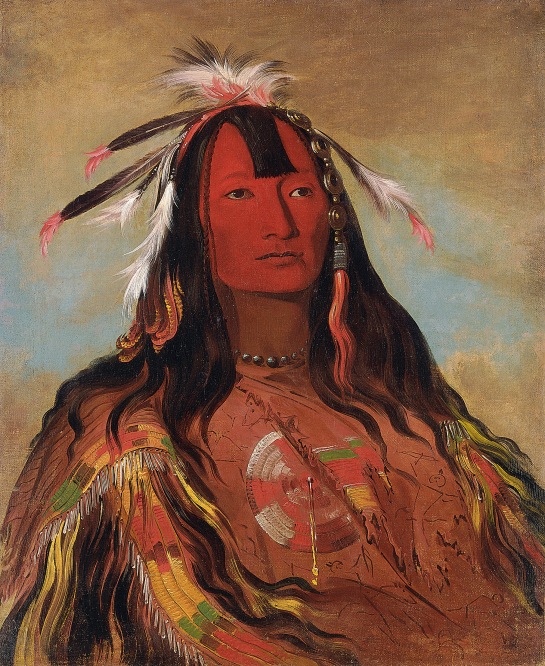

Hee-oh’ks-te-kin, Rabbit’s Skin Leggings, a Brave Nez Percé,

George Catlin, 1832, ©Smithsonian American Art Museum

It’s a fairly rare occurrence when I find myself in London with nothing specific to do. Living in Kent but working in London I’m almost always en route to something pre-planned. But when such a lovely occasion does arise I am almost overwhelmed by the possibilities and can feel myself potentially heading into headless chicken mode, unable to make a sound decision due to an over-abundance of choices. On this last particular rainy Tuesday in London I had only an hour to spare and an empty pocket. Standing in St Martin’s Lane I made the decision to develop my underused sketchbook within the confines of the National Portrait Gallery, not a very regular haunt of mine and so a welcome change. Climbing the marble staircase I was pleasantly surprised to spot that the current exhibition is in fact free and, as it turns out, more than worth a visit.

George Catlin’s portraits of Native American Indians are both strikingly powerful and sinisterly suspicious. I was shocked initially by the wall text which stated that Catlin’s images are almost unique, a rare insight into the life inside the tribe and as such, largely what our representations of Native American Indians are still based on today. It could well be the cynic in me, but at a time when Native American Indians were considered savages and being driven from their homes and their settlements, how likely is it really that a white American contemporary could paint them and their lifestyles entirely unbiased by his own experience?

I’m not the only one to have thought this of course, even those at the time accused Catlin of exaggerating for effect which, if true, casts doubt on the accuracy of his portrayals. Although there is no reason to suggest that Catlin had entirely, lets say, unsavoury motives, it’s almost certain he was not acting purely in the interests of the Indians. As the exhibition points out, Catlin was, as well as being an ambitious painter, of an entrepreneurial nature. Working hard to get himself established he set up his own shows, made continuous and increasingly desperate efforts to sell his Native American Indian collection and highlighted the sensational aspects of his experiences to acquire an audience. He did, in effect, exploit the culture he claimed he was trying to protect. Certain members of the tribes were understandably wary of trusting and becoming involved with a white outsider but, after seeing others pose for portraits, became intrigued and were won over. Catlin’s practice, well, portraiture in general I suppose, does appeal to some of the less impressive aspects of human nature; vanity, power, self-importance. He essentially infiltrated them, infecting both them and their culture with practices embodying western concepts and hierarchies. He wasn’t the only one. Not the first and certainly not the last.

It’s possible, or even likely that Catlin proceeded with generally good intentions but, like many philanthropic objectives, ended up being patronising and ultimately damaging. His work Wi-jún-jon, Pigeon’s Egg Head (The Light) Going To and Returning From Washington is clearly a morality tale, intentional propaganda for the good of the tribesmen. A tribe member posing in traditional dress is shown on one half of the canvas alongside a portrayal of the same man on his return from treaty talks in Washington; suited, swaggering and complete with cane and pipe. Catlin, in his eagerness to captivate his audience at home and to commercialise the image of the Native American Indian people, succeeded in using them for his own advancement.

The paintings themselves are spellbinding. Entirely accurate or not, an overwhelming sense of personality radiates from the works, each, despite western poses and potentially characterised representation, conveying the depth inherent in a people whose history outranks the immigrant Americans by thousands of years. The voyeuristic, sensationalist aspect of their attraction is still relevant, the brilliance and beauty of their dress still captivating. Whether or not we believe he was truly a force for the good of the tribesmen themselves, we can’t deny that his paintings brim over with an intensity of expression and now, as then, do not fail to mesmerize their audience.

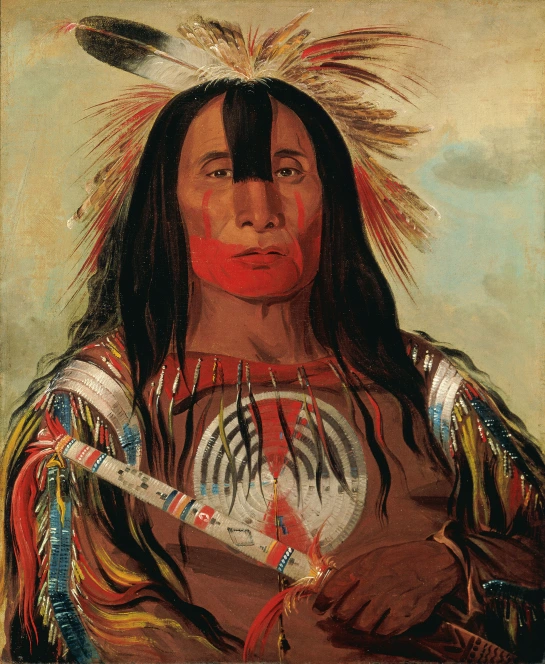

La-dóo-ke-a, Buffalo Bull, a Grand Pawnee Warrior Pawnee,

George Catlin, 1832, ©Smithsonian American Art Museum

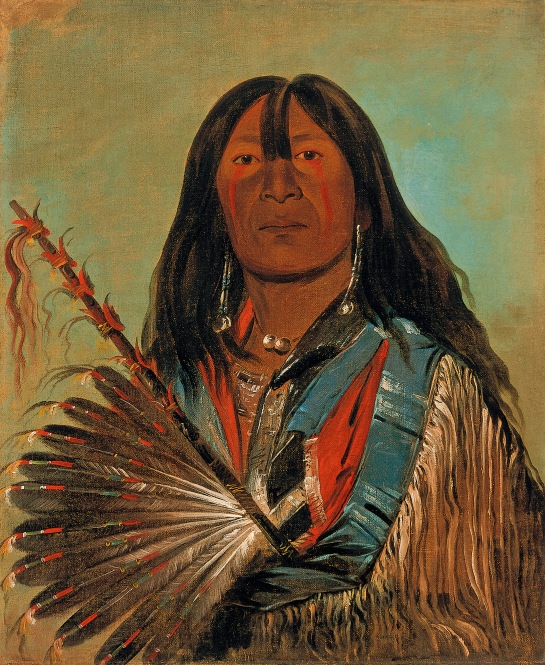

Stu-mick-o-súcks, Buffalo Bull’s Back Fat, Head Chief, Blood Tribe Blackfoot/Kainai,

George Catlin, 1832, ©Smithsonian American Art Museum

Medicine Man, Performing his Mysteries over a Dying Man Blackfoot/Siksika,

George Catlin, 1832, ©Smithsonian American Art Museum

Eeh-nís-kim, Crystal Stone, Wife of the Chief Blackfoot/Kainai,

George Catlin, 1832, ©Smithsonian American Art Museum

Shón-ka, The Dog, Chief of the Bad Arrow Points Band Western Sioux/Lakota,

George Catlin, 1832, ©Smithsonian American Art Museum

George Catlin – American Indian Portraits is showing at the National Portrait Gallery until 23rd June and is free entry.

Somewhat unsurprisingly the area around Piccadilly is not one of my usual haunts; the Ritz and the Wolseley being just a tad out of my price range, and even further out of my interest range. Being more of a Camden girl myself, were it not for the lure of David Harkins’ recent exhibition at Bury Street I may never have stepped past that territory of the super-rich, to discover that just beyond is hidden a veritable wealth of artworks, bustling for space in the innumerable galleries which line the back lanes.

I recently found myself squeezed amongst a lively throng inside a single element of this compound treasure trove; a beautifully intimate gallery at 3 Bury Street. Artist, actor, and probation officer, David Harkins’ work is an immediate delight to the inquisitive eye. In terms of physical scale his pieces are relatively small, and so when hung create an astounding aesthetic of contrasting and collaborating imagery spread across the wall like a huge, woven patchwork quilt. A tapestry of individual stories.

Indian Mathematics is instantly reminiscent of Miro, with its deep swirling blues which begin to swallow the splashes of colour above; seemingly dissolving before your eyes into the canvas. The titles add another dimension to the paintings, leading your senses towards a subconscious aspect you may not have explored; their playful suggestiveness mirroring the dreamlike theme running through pieces such as An Admission and Egyptian Headstand, where dominant forms and intricate paintwork create a weave of storytelling. A distinctive thread running through the series is the horizontal line. Drawing the eye across the canvas it moves toward the continuation of the story, past the boundaries of the surface. Within the abstract pieces this linear tool conjures landscape, providing spatial forms which determine a perspective focus for the viewer and work together with other patterns such as the mountainous triangular shapes in Crowns, or Emergency Ponchos.

Turning around the room and stretching to place my line of sight above the mass of heads at the opening night, I began to discern a sense of the time spent creating this series of works. A period of exploration seems to come across, of pushing the boundaries of experience and comfort. Indeed, speaking to a fellow observer I was told that David’s previous work is far more abstract. His use of figuration and narrative in this show mark a new period of experimentation where monochrome abounds and materials in collage writhe in and out of the 2D boundaries. However, although the meditative narrative may draw us through lighthearted stories, there are also explicit elements of darkness. The use of the black and white palette and mono-printing technique strips away the detail of other works and returns us to a raw, expressive language. Here the lines reappear, possibly suggesting the bars of a prison in a reference to David’s work as a probation officer. The figures which feature are also noticeably alone and sometimes with explicitly negative emotions, as in The Anxious Man, an astute capturing of melancholy tension.

David Harkin’s art seems to draw influence from a unique collaboration of various styles. A strong tribal element runs throughout; bold, powerful, colourful and symbolic, yet there are plenty of moments of quiet tenderness, delicately intertwined with the understated storytelling of a thinker, a seer. Humour abounds. Tongue-in-cheek motifs use the force of simple production and dark satirical undertones to create powerful impact in works such as A Saint in Wolf’s Clothing. I clearly wasn’t the only one to have been absorbed into David’s brushstrokes and collages. As the stickers flew on and the works flew off the walls, I thanked my lucky stars I had been quick enough to grab Crowns, my first (and undoubtedly favourite) Christmas present of 2012. Pressing my way through the crowd towards the exit, like Indiana Jones having acquired his fought-for treasures, I knew this would not be the last I saw of David Harkins. I think I can guarantee the same for you.

For more information on David’s work see his website here

Photographs by Alex Bamford

It is rare that an artist can transform a space such as the galleries at Tate Modern; rarer still to transform you, within it, into an entirely different state of mind; and even rarer to achieve these with purely 2D media. But Edvard Munch, along with the curators at Tate, has done just that.

The new Munch retrospective opened last week, following the extremely opportune timing of The Scream 1893 auctioning, which propelled the painter to the forefront of current public interest. Not that Munch has ever really been forgotten; The Scream is endlessly parodied across all art forms. It is a shame though to think of the many disappointed faces when they realise that neither the scream is on show, nor the Madonna 1894-5, another classic Munch. However I feel quite sure that any initial frozen smiles will soon melt to real furrowed brows of concentration and absorption as visitors get whisked away into Munch’s dreamlike world.

Initially, in this William Blake-esque setting, where pronounced yet unstable verticals abound and focus refuses to submit to standard optics, you feel somewhat comfortable; as if a traveller in a pastoral narrative. Then you notice that the couple you spotted kissing tenderly is named Vampyr 1893-4, and the mother and child sharing an embrace is titled The Sick Child 1885-7. As if in a dream, comfort and menace intertwine; contrasting versions of works are displayed facing one another with you suspended in the middle, caught up in a fundamental struggle which permeates the rest of the paintings.

One of the most fascinating elements of this show is the photographic experimentation and documentation of Munch’s interest in the new pioneering visual machines. Photography was relatively new at the time; Kodak had developed the first mass-marketed camera in 1901 – the Brownie. The sometimes transcendental effect of the photographs, created through over-exposure and double negatives, tied in with Munch’s own curiosity about spirituality as well as giving him an outlet for self-reflection. Munch dealt with an inner struggle, a fact which is well-documented due to his breakdown in later life, and threads of these issues do seem to shine through in his work. Looking through his photographs I felt a sudden concern that these images felt inherently personal. Much like the public/private battle of Gillian Wearing, I was torn between the fascination of voyeuristic intrigue and the moral inhibition around questions of personal privacy. Did Munch want these to be on show? Some show him in strange poses, and even naked; were they intended for public consumption or were they an intimate exploration of self?

One theme which repeats throughout his paintings is that of the outward gaze. I call it a gaze, when what I really mean is a stare. Often threatening, sometimes unsettling, but usually menacing. Rarely does a figure smile at the viewer from the canvas. Paintings such as Workers on their way home ’13-14 portray frightening and aggressive stances towards the viewer. Was this how Munch saw the world? Are we the figure in the painting or is he? This motif continues in The Artist and his Model ’19-21, Murder on the Road ’19 and Red Virginia Creeper ’88-89 and creates an unsettling tension between viewer and painting. In Street in Asgardstrand ’01, the figure is there, albeit not so seemingly malevolent; but its very situation and directness still set the viewer on edge. In the background, roads and pathways regularly appear, perhaps signifying ways to escape from his own state of mind. A group of people are often nearer to the path, but the solitary figure in the foreground remains, fixed and looking out from the frame; the way is there, but only in the peripheral.

Throughout the exhibition I felt the overwhelming sense of an artist ahead of his time. Despite the obvious influence of the Impressionist movement on his work, with its veritable myriad of conspicuous brushstrokes and deep variation of tone and colour, Munch’s ability to communicate tension through style and medium is sometimes reminiscent of very modern day artists. In Self-Portrait Facing Left ’12-13, he uses woodcutting to create a representation of self-image through a series of disconcertingly violent scratches. The composition of the piece I found reminiscent of Francis Bacon, creating form and raw emotion with fast movements. No wonder they named him an Expressionist. His Kiss in the Fields ’43 is intrinsically minimalist; the natural texture and grain of the wood contrasting against the sharp, imposed scoring of the suggested coupling. This piece could sit quite inconspicuously in a modern art gallery. Another of his pieces which could easily blend into not just a gallery, but a specific exhibition, is Yellow Log ’12. Anyone who saw the recent David Hockney exhibition at the Royal Academy could not fail to spot the extreme similarity between this motif and Hockney’s newer works; the comparisons are there in colour, form, style and technique.

I hope that both Hockney and Bacon, as well as many other artists, would happily admit their debt to this great painter (Hockney for one could hardly deny it). His skill in conveying memories and emotions as almost lost in that moment between dream and wake; his ability to pick out the sharp points in those hazes, whilst still rendering the featureless forms in the background with inherent purpose. Towards the end of his life these nightmarish scenarios became reality for a period during his breakdown, in this period his paintings became less concerned with faceless shadows in the peripheral and more of a confrontation with solitary mortality. His work continues to fascinate us, and not just because he provides an insight into mental illness, but because we recognise his universal struggle with the human condition.