George Catlin – Fighting for culture or grasping for fame?

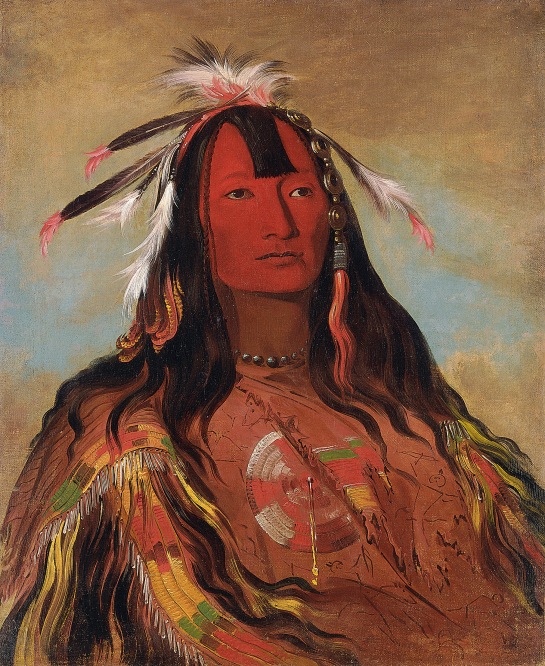

Hee-oh’ks-te-kin, Rabbit’s Skin Leggings, a Brave Nez Percé,

George Catlin, 1832, ©Smithsonian American Art Museum

It’s a fairly rare occurrence when I find myself in London with nothing specific to do. Living in Kent but working in London I’m almost always en route to something pre-planned. But when such a lovely occasion does arise I am almost overwhelmed by the possibilities and can feel myself potentially heading into headless chicken mode, unable to make a sound decision due to an over-abundance of choices. On this last particular rainy Tuesday in London I had only an hour to spare and an empty pocket. Standing in St Martin’s Lane I made the decision to develop my underused sketchbook within the confines of the National Portrait Gallery, not a very regular haunt of mine and so a welcome change. Climbing the marble staircase I was pleasantly surprised to spot that the current exhibition is in fact free and, as it turns out, more than worth a visit.

George Catlin’s portraits of Native American Indians are both strikingly powerful and sinisterly suspicious. I was shocked initially by the wall text which stated that Catlin’s images are almost unique, a rare insight into the life inside the tribe and as such, largely what our representations of Native American Indians are still based on today. It could well be the cynic in me, but at a time when Native American Indians were considered savages and being driven from their homes and their settlements, how likely is it really that a white American contemporary could paint them and their lifestyles entirely unbiased by his own experience?

I’m not the only one to have thought this of course, even those at the time accused Catlin of exaggerating for effect which, if true, casts doubt on the accuracy of his portrayals. Although there is no reason to suggest that Catlin had entirely, lets say, unsavoury motives, it’s almost certain he was not acting purely in the interests of the Indians. As the exhibition points out, Catlin was, as well as being an ambitious painter, of an entrepreneurial nature. Working hard to get himself established he set up his own shows, made continuous and increasingly desperate efforts to sell his Native American Indian collection and highlighted the sensational aspects of his experiences to acquire an audience. He did, in effect, exploit the culture he claimed he was trying to protect. Certain members of the tribes were understandably wary of trusting and becoming involved with a white outsider but, after seeing others pose for portraits, became intrigued and were won over. Catlin’s practice, well, portraiture in general I suppose, does appeal to some of the less impressive aspects of human nature; vanity, power, self-importance. He essentially infiltrated them, infecting both them and their culture with practices embodying western concepts and hierarchies. He wasn’t the only one. Not the first and certainly not the last.

It’s possible, or even likely that Catlin proceeded with generally good intentions but, like many philanthropic objectives, ended up being patronising and ultimately damaging. His work Wi-jún-jon, Pigeon’s Egg Head (The Light) Going To and Returning From Washington is clearly a morality tale, intentional propaganda for the good of the tribesmen. A tribe member posing in traditional dress is shown on one half of the canvas alongside a portrayal of the same man on his return from treaty talks in Washington; suited, swaggering and complete with cane and pipe. Catlin, in his eagerness to captivate his audience at home and to commercialise the image of the Native American Indian people, succeeded in using them for his own advancement.

The paintings themselves are spellbinding. Entirely accurate or not, an overwhelming sense of personality radiates from the works, each, despite western poses and potentially characterised representation, conveying the depth inherent in a people whose history outranks the immigrant Americans by thousands of years. The voyeuristic, sensationalist aspect of their attraction is still relevant, the brilliance and beauty of their dress still captivating. Whether or not we believe he was truly a force for the good of the tribesmen themselves, we can’t deny that his paintings brim over with an intensity of expression and now, as then, do not fail to mesmerize their audience.

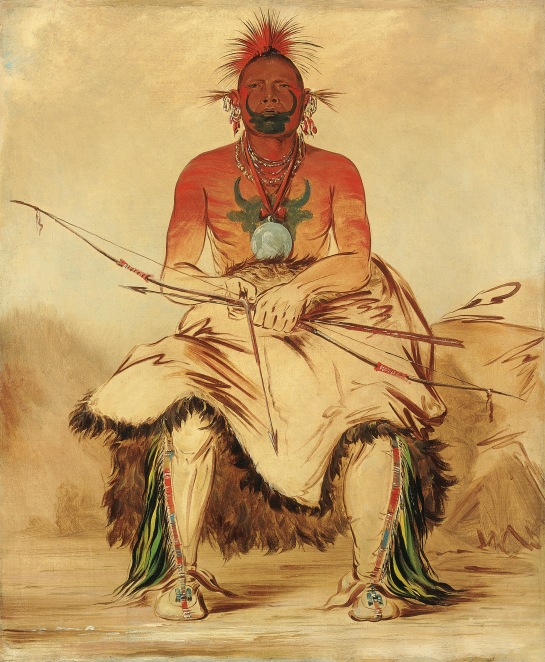

La-dóo-ke-a, Buffalo Bull, a Grand Pawnee Warrior Pawnee,

George Catlin, 1832, ©Smithsonian American Art Museum

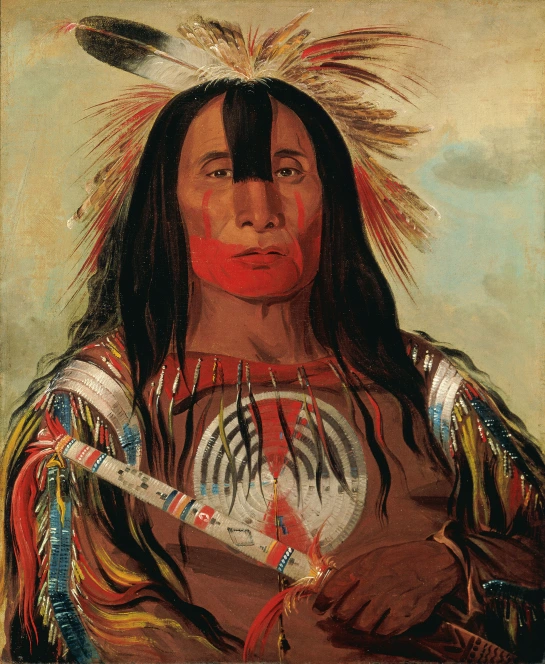

Stu-mick-o-súcks, Buffalo Bull’s Back Fat, Head Chief, Blood Tribe Blackfoot/Kainai,

George Catlin, 1832, ©Smithsonian American Art Museum

Medicine Man, Performing his Mysteries over a Dying Man Blackfoot/Siksika,

George Catlin, 1832, ©Smithsonian American Art Museum

Eeh-nís-kim, Crystal Stone, Wife of the Chief Blackfoot/Kainai,

George Catlin, 1832, ©Smithsonian American Art Museum

Shón-ka, The Dog, Chief of the Bad Arrow Points Band Western Sioux/Lakota,

George Catlin, 1832, ©Smithsonian American Art Museum

George Catlin – American Indian Portraits is showing at the National Portrait Gallery until 23rd June and is free entry.

Leaving aside the trope of the “noble savage” so deeply entrenched in Catlin’s work, his depictions of dress, markings, jewelry, and other aspects of material culture are an unmatched resource for ethnohistorians interested in the 19th century. I disapprove of Catlin’s motives and prejudices, but I can’t help but value his results. Great post!

I concur!!