One of my favourite things about this idiosyncratic little Isle we call the UK is the quintessential seaside town. There are few other things which encapsulate so specifically the unique facets of the British psyche into one small microcosmic burst of sublime kitsch consumerism, freezing waters lapping on dirty beaches and cheap, melting ice cream cones (with a flake, of course). It’s fabulous. Tasteful is sometimes lovely; a middle-class cup of Earl Grey on a Victorian garden terrace in Cambridge can be all well and good, but really it has comparatively little soul. Stick me on Margate beach surrounded by gobby kids with parents no less refined, half-blinded by the reflections from the arcade frontages which prove that all which glitters is definitely not gold, and I’m in my element. I can’t help but assume you are all suspecting that I am a typical product of my upbringing in this respect. That I relish these, to some, distasteful scenes with glee because of their centrality to the 1980’s childhood of a working class Southerner. Correct. But it is not only this geographical circumstance of birth which causes me to grin as soon as my internal satnav senses I am within 10 miles of a sugared doughnut shack; British seasides truly are on their own merit singularly enjoyable.

Growing up in Dartford in the 80’s and 90’s, Margate was our closest beach and still a fairly thriving hive of domestic tourism at that point. We would plead with our parents to take us there, as yet uninterested in foreign climes or the lure of saccharine Disney marketing. The swingboats at Margate beach were the highlight of our summer. How tantalisingly simple life was then! As we got older, Dreamland, that disintegrating grandfather of theme parks, became the focus of our pubescent attentions. The lure of its death-defyingly ancient roller-coaster structures stoking the fire of our naive, thrill-seeking bellies. The what we considered subtle experimentation with the mating ritual, (which in hindsight consisted entirely of stalking a group of usually slightly older boys, acting as if we hadn’t noticed them and reaching the end of a whole day having never actually spoken to them) was played out around the grounds of Dreamland like groundhog day. We could get angsty conversational mileage from that kind of near-encounter for days.

Then one fateful day Dreamland surrendered to the inevitable and impending padlock of the health and safety regulators. A thousand teenagers loitered, bereft, with only the arcades for entertainment. But soon these began to wither away too, the effect of the 1960s emergence of cheap package holidays abroad becoming visible on the face of the town. Less families, less fun, less income; more unemployment, more pound shops, more crime. Seaside towns have always been particularly vulnerable to the effects of economic shift; their seasonal nature meaning winter is often as bleak as summer is bright. But there came upon British seafronts in that era a tidal wave of degradation, half-empty swingboats standing then as monuments to a lost age of contentedness.

Margate soon became known to those who hadn’t spent childhood days there as a bit of a dive, its slightly more well-to-do neighbour Ramsgate wringing the mileage out of its nouveau-riche marina facade and characterless wine bars, attempting to emulate the seafront harbours of its continental competitors. Margate stuck to its guns; sun, sea, sand and some truly great fish ‘n’ chips. As with so many other nearby towns it is now only just starting to see some semblance of a recovery. Interestingly, this regeneration is seemingly part of a pattern; a swathe of curious ‘cultural quarters’ beginning to emerge from the wind-battered frontages of these former summer holiday havens. Folkestone, Margate, Dungeness; all have been sprinkled with a relatively recent dusting of artistic and culturally important spectacle. Without further research I can only speculate as to why this might be, but educated guesswork would lead me to suggest the gradual migration of the middle classes from London might have had at least a partial impact. Commuter towns now reach even as far as the southern coast, much as a result of the bordering areas outside London observing a continuing rise in living costs. It’s obvious then (to some councils at least!) that you would try to appeal to the interests and expectations of London commuters; to put in the worthwhile effort and investment which might encourage them to stay in your culture-rich but comparatively affordable and close to home surroundings.

Down at Margate, the most visible and high-profile evidence of this artistic injection is the new Turner Contemporary, all classic Chipperfield wide and light exhibition spaces and orgasmic interspatial elements. But it may not hold this title for long; I hear on the grapevine a most exciting rumour. It seems grandfather time may rewind his clock for Margate and resurrect my childhood pleasure park, Dreamland, like an old but cocksure phoenix ready to swagger back into the consciousness of the town.

Of course the obvious artistic link to Margate is through someone who may well not agree with my sickly-sweet love for it; Mad Tracey from Margate, aka 90’s artworld darling and one of my personal favourites, Tracey Emin, her often biographical works shocking staunch upholders of the British taboo with graphic representations of the gritty side of life in the town during its decline. Or maybe she would? Without her difficult upbringing amidst the area’s grim social scene and degenerate male contingent would she ever have achieved such fame and fortune? Tracey Emin’s wistful recollections of the area in her artworks have greatly influenced how much I enjoy her work. Aside from respecting the brutal honesty of her cathartic subject-matters and refusal to bow to the mummified art establishment, I feel an affinity with her attachment to the town in which I spent countless fun-filled days circa 1989.

It seems almost bizarre to me that I will soon be showing 3 of my own photographs in one of the new art galleries in this town for which I hold such affection. Aside from the encouraging fact that these modern and exciting spaces now exist there at all, it’s interesting that artists from the South-East are coming to Margate to exhibit instead of heading into London and seems to me indicative of a gradual shift in collective focus onto non London-based art. It’s high time we began to look locally at the wealth of unrecognised and underdeveloped artistic talent on our doorstep, not solely in my hometown of Dartford and around Kent but further out and beyond. London art has been done to death, let the artistic era of the provinces commence!

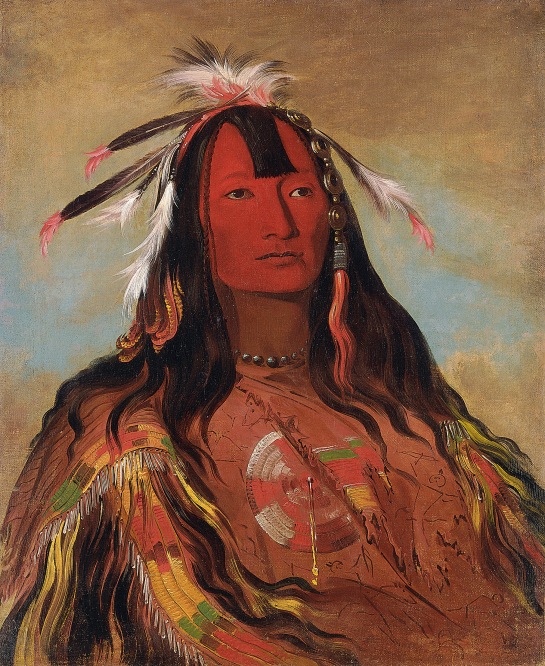

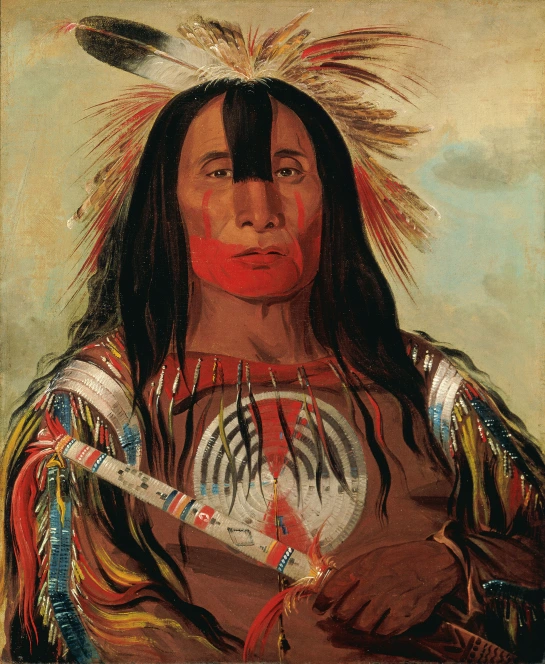

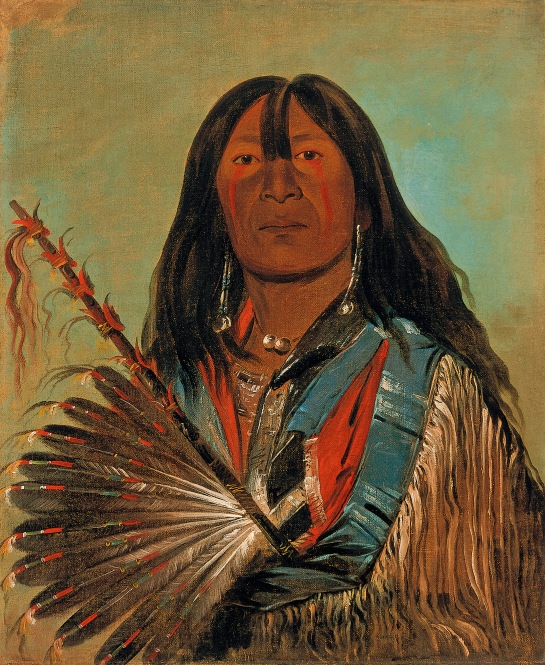

A selection of my photographs will be shown, along with the work of some of my fellow Dartford Arts Network members (Kasia Kat Parker & David Houston), as part of an exhibition primarily featuring the paintings of Tunde Odelade at the Pie Factory Gallery in Margate. The exhibition runs from 8th May – 21st May and is free to visit. For directions and further information see their website and if you’re in the area on 10th May do come in and say hi – I’ll be there milling around from 10am – 6pm.